Convergence of Fourier series

In mathematics, the question of whether the Fourier series of a periodic function converges to the given function is researched by a field known as classical harmonic analysis, a branch of pure mathematics. Convergence is not necessarily a given in the general case, and there are criteria which need to be met in order for convergence to occur.

Determination of convergence requires the comprehension of pointwise convergence, uniform convergence, absolute convergence, Lp spaces, summability methods and the Cesàro mean.

Contents |

Preliminaries

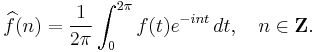

Consider ƒ an integrable function on the interval [0,2π]. For such an ƒ the Fourier coefficients  are defined by the formula

are defined by the formula

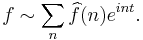

It is common to describe the connection between ƒ and its Fourier series by

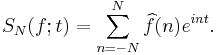

The notation ~ here means that the sum represents the function in some sense. In order to investigate this more carefully, the partial sums need to be defined:

The question we will be interested in is: do the functions  (which are functions of the variable t we omitted in the notation) converge to ƒ and in which sense? Are there conditions on ƒ ensuring this or that type of convergence? This is the main problem discussed in this article.

(which are functions of the variable t we omitted in the notation) converge to ƒ and in which sense? Are there conditions on ƒ ensuring this or that type of convergence? This is the main problem discussed in this article.

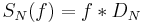

Before continuing the Dirichlet's kernel needs to be introduced. Taking the formula for  , inserting it into the formula for

, inserting it into the formula for  and doing some algebra will give that

and doing some algebra will give that

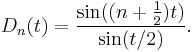

where ∗ stands for the periodic convolution and  is the Dirichlet kernel which has an explicit formula,

is the Dirichlet kernel which has an explicit formula,

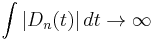

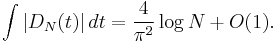

The Dirichlet kernel is not a positive kernel, and in fact, its norm diverges, namely

a fact that will play a crucial role in the discussion. The norm of Dn in L1(T) coincides with the norm of the convolution operator with Dn, acting on the space C(T) of periodic continuous functions, or with the norm of the linear functional ƒ → (Snƒ)(0) on C(T). Hence, this family of linear functionals on C(T) is unbounded, when n → ∞.

Magnitude of Fourier coefficients

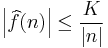

In applications, it is often useful to know the size of the Fourier coefficient.

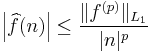

If  is an absolutely continuous function,

is an absolutely continuous function,

for  a constant that only depends on

a constant that only depends on  .

.

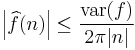

If  is a bounded variation function,

is a bounded variation function,

If

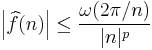

If  and

and  has modulus of continuity

has modulus of continuity  ,

,

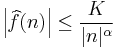

and therefore, if  is in the α-Hölder class

is in the α-Hölder class

Pointwise convergence

There are many known sufficient conditions for the Fourier series of a function to converge at a given point x, for example if the function is differentiable at x. Even a jump discontinuity does not pose a problem: if the function has left and right derivatives at x, then the Fourier series will converge to the average of the left and right limits (but see Gibbs phenomenon).

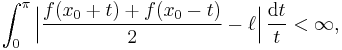

The Dirichlet–Dini Criterion states that: if ƒ is 2π–periodic, locally integrable and satisfies

then (Snƒ)(x0) converges to ℓ. This implies that for any function ƒ of any Hölder class α > 0, the Fourier series converges everywhere to ƒ(x).

It is also known that for any periodic function of bounded variation, the Fourier series converges everywhere. See also Dini test.

There exists a continuous function whose Fourier series converges pointwise, but not uniformly; see Antoni Zygmund, Trigonometric Series, vol. 1, Chapter 8, Theorem 1.13, p. 300.

However, the Fourier series of a continuous function need not converge pointwise. Perhaps the easiest proof uses the non-boundedness of Dirichlet's kernel in L1(T) and the Banach–Steinhaus uniform boundedness principle. As typical for existence arguments invoking the Baire category theorem, this proof is nonconstructive. It shows that the family of continuous functions whose Fourier series converges at a given x is of first Baire category, in the Banach space of continuous functions on the circle. So in some sense pointwise convergence is atypical, and for most continuous functions the Fourier series does not converge at a given point. However Carleson's theorem shows that for a given continuous function the Fourier series converges almost everywhere.

Uniform convergence

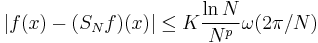

Suppose  , and

, and  has modulus of continuity

has modulus of continuity  (we assume here that

(we assume here that  is also non decreasing), then the partial sum of the Fourier series converges to the function with the following speed

is also non decreasing), then the partial sum of the Fourier series converges to the function with the following speed

for a constant  that does not depend upon

that does not depend upon  , nor

, nor  , nor

, nor  .

.

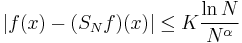

This theorem, first proved by D Jackson, tells, for example, that if  satisfies the

satisfies the  -Hölder condition, then

-Hölder condition, then

If  is

is  periodic and absolutely continuous on

periodic and absolutely continuous on ![[0,2\pi]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/58c9a5de0cb1a343ae0acd1fb191eea1.png) , then the Fourier series of

, then the Fourier series of  converges uniformly, but not necessarily absolutely, to

converges uniformly, but not necessarily absolutely, to  , see p. 519 Exercise 6 (d) and p. 520 Exercise 7 (c), Introduction to classical real analysis, by Karl R. Stromberg, 1981.

, see p. 519 Exercise 6 (d) and p. 520 Exercise 7 (c), Introduction to classical real analysis, by Karl R. Stromberg, 1981.

Absolute convergence

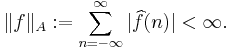

A function ƒ has an absolutely converging Fourier series if

Obviously, if this condition holds then  converges absolutely for every t and on the other hand, it is enough that

converges absolutely for every t and on the other hand, it is enough that  converges absolutely for even one t, then this condition will hold. In other words, for absolute convergence there is no issue of where the sum converges absolutely — if it converges absolutely at one point then it does it everywhere.

converges absolutely for even one t, then this condition will hold. In other words, for absolute convergence there is no issue of where the sum converges absolutely — if it converges absolutely at one point then it does it everywhere.

The family of all functions with absolutely converging Fourier series is a Banach algebra (the operation of multiplication in the algebra is a simple multiplication of functions). It is called the Wiener algebra, after Norbert Wiener, who proved that if ƒ has absolutely converging Fourier series and is never zero, then 1/ƒ has absolutely converging Fourier series. The original proof of Wiener's theorem was difficult; a simplification using the theory of Banach algebras was given by Israel Gelfand. Finally, a short elementary proof was given by Donald J. Newman in 1975.

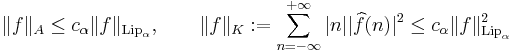

If  belongs to a α-Hölder class for α > ½ then

belongs to a α-Hölder class for α > ½ then

for  the constant in the Hölder condition,

the constant in the Hölder condition,  a constant only dependent on

a constant only dependent on  ;

;  is the norm of the Krein algebra. Notice that the ½ here is essential — there are ½-Hölder functions which do not belong to the Wiener algebra. Besides, this theorem cannot improve the best known bound on the size of the Fourier coefficient of a α-Hölder function - that is only O

is the norm of the Krein algebra. Notice that the ½ here is essential — there are ½-Hölder functions which do not belong to the Wiener algebra. Besides, this theorem cannot improve the best known bound on the size of the Fourier coefficient of a α-Hölder function - that is only O and then not summable!

and then not summable!

If ƒ is of bounded variation and belongs to a α-Hölder class for some α > 0, it belongs to the Wiener algebra.

Norm convergence

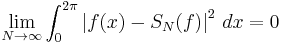

The simplest case is that of L2, which is a direct transcription of general Hilbert space results. According to the Riesz–Fischer theorem, if ƒ is square-integrable then

i.e.,  converges to ƒ in the norm of L2. It is easy to see that the converse is also true: if the limit above is zero, ƒ must be in L2. So this is an if and only if condition.

converges to ƒ in the norm of L2. It is easy to see that the converse is also true: if the limit above is zero, ƒ must be in L2. So this is an if and only if condition.

If 2 in the exponents above is replaced with some p, the question becomes much harder. It turns out that the convergence still holds if 1 < p < ∞. In other words, for ƒ in Lp,  converges to ƒ in the Lp norm. The original proof uses properties of holomorphic functions and Hardy spaces, and another proof, due to Salomon Bochner relies upon the Riesz–Thorin interpolation theorem. For p = 1 and infinity, the result is not true. The construction of an example of divergence in L1 was first done by Andrey Kolmogorov (see below). For infinity, the result is a more or less trivial corollary of the uniform boundedness principle.

converges to ƒ in the Lp norm. The original proof uses properties of holomorphic functions and Hardy spaces, and another proof, due to Salomon Bochner relies upon the Riesz–Thorin interpolation theorem. For p = 1 and infinity, the result is not true. The construction of an example of divergence in L1 was first done by Andrey Kolmogorov (see below). For infinity, the result is a more or less trivial corollary of the uniform boundedness principle.

If the partial summation operator SN is replaced by a suitable summability kernel (for example the Fejér sum obtained by convolution with the Fejér kernel), basic functional analytic techniques can be applied to show that norm convergence holds for 1 ≤ p < ∞.

Convergence almost everywhere

The problem whether the Fourier series of any continuous function converges almost everywhere was posed by Nikolai Lusin in the 1920s and remained open until finally resolved positively in 1966 by Lennart Carleson. Indeed, Carleson showed that the Fourier expansion of any function in L2 converges almost everywhere. This result is now known as Carleson's theorem. Later on Richard Hunt generalized this to Lp for any p > 1. Despite a number of attempts at simplifying the proof, it is still one of the most difficult results in analysis.

Contrariwise, Andrey Kolmogorov, in his very first paper published when he was 21, constructed an example of a function in L1 whose Fourier series diverges almost everywhere (later improved to divergence everywhere).

It might be interesting to note that Jean-Pierre Kahane and Yitzhak Katznelson proved that for any given set E of measure zero, there exists a continuous function ƒ such that the Fourier series of ƒ fails to converge on any point of E.

Summability

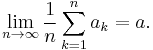

Does the sequence 0,1,0,1,0,1,... (the partial sums of Grandi's series) converge to ½? This does not seem like a very unreasonable generalization of the notion of convergence. Hence we say that any sequence  is Cesàro summable to some a if

is Cesàro summable to some a if

It is not difficult to see that if a sequence converges to some a then it is also Cesàro summable to it.

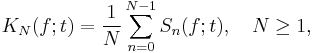

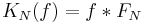

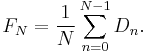

To discuss summability of Fourier series, we must replace  with an appropriate notion. Hence we define

with an appropriate notion. Hence we define

and ask: does  converge to f?

converge to f?  is no longer associated with Dirichlet's kernel, but with Fejér's kernel, namely

is no longer associated with Dirichlet's kernel, but with Fejér's kernel, namely

where  is Fejér's kernel,

is Fejér's kernel,

The main difference is that Fejér's kernel is a positive kernel. Fejér's theorem states that the above sequence of partial sums converge uniformly to ƒ. This implies much better convergence properties

- If ƒ is continuous at t then the Fourier series of ƒ is summable at t to ƒ(t). If ƒ is continuous, its Fourier series is uniformly summable (i.e.

converges uniformly to ƒ).

converges uniformly to ƒ). - For any integrable ƒ,

converges to ƒ in the

converges to ƒ in the  norm.

norm. - There is no Gibbs phenomenon.

Results about summability can also imply results about regular convergence. For example, we learn that if ƒ is continuous at t, then the Fourier series of ƒ cannot converge to a value different from ƒ(t). It may either converge to ƒ(t) or diverge. This is because, if  converges to some value x, it is also summable to it, so from the first summability property above, x = ƒ(t).

converges to some value x, it is also summable to it, so from the first summability property above, x = ƒ(t).

Order of growth

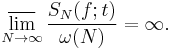

The order of growth of Dirichlet's kernel is logarithmic, i.e.

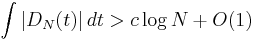

See Big O notation for the notation O(1). It should be noted that the actual value  is both difficult to calculate (see Zygmund 8.3) and of almost no use. The fact that for some constant c we have

is both difficult to calculate (see Zygmund 8.3) and of almost no use. The fact that for some constant c we have

is quite clear when one examines the graph of Dirichlet's kernel. The integral over the n-th peak is bigger than c/n and therefore the estimate for the harmonic sum gives the logarithmic estimate.

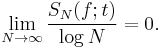

This estimate entails quantitative versions of some of the previous results. For any continuous function f and any t one has

However, for any order of growth ω(n) smaller than log, this no longer holds and it is possible to find a continuous function f such that for some t,

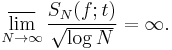

The equivalent problem for divergence everywhere is open. Sergei Konyagin managed to construct an integrable function such that for every t one has

It is not known whether this example is best possible. The only bound from the other direction known is log n.

Multiple dimensions

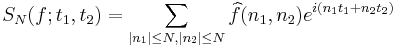

Upon examining the equivalent problem in more than one dimension, it is necessary to specify the precise order of summation one uses. For example, in two dimensions, one may define

which are known as "square partial sums". Replacing the sum above with

lead to "circular partial sums". The difference between these two definitions is quite notable. For example, the norm of the corresponding Dirichlet kernel for square partial sums is of the order of  while for circular partial sums it is of the order of

while for circular partial sums it is of the order of  .

.

Many of the results true for one dimension are wrong or unknown in multiple dimensions. In particular, the equivalent of Carleson's theorem is still open for circular partial sums. Almost everywhere convergence of "square partial sums" (as well as more general polygonal partial sums) in multiple dimensions was established around 1970 by Charles Fefferman.

References

Textbooks

- Dunham Jackson "The theory of Approximation", AMS Colloquium Publication Volume XI, New York 1930.

- Nina K. Bary, A treatise on trigonometric series, Vols. I, II. Authorized translation by Margaret F. Mullins. A Pergamon Press Book. The Macmillan Co., New York 1964.

- Antoni Zygmund, Trigonometric series, Vol. I, II. Third edition. With a foreword by Robert A. Fefferman. Cambridge Mathematical Library. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002. ISBN 0-521-89053-5

- Yitzhak Katznelson, An introduction to harmonic analysis, Third edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004. ISBN 0-521-54359-2

- Karl R. Stromberg, "Introduction to classical analysis", Wadsworth International Group, 1981. ISBN 0-534-98012-0

- The Katznelson book is the one using the most modern terminology and style of the three. The original publishing dates are: Zygmund in 1935, Bari in 1961 and Katznelson in 1968. Zygmund's book was greatly expanded in its second publishing in 1959, however.

Articles referred to in the text

- Paul du Bois Reymond, Ueber die Fourierschen Reihen, Nachr. Kön. Ges. Wiss. Göttingen 21 (1873), 571–582.

- This is the first proof that the Fourier series of a continuous function might diverge. In German

- Andrey Kolmogorov, Une série de Fourier–Lebesgue divergente presque partout, Fundamenta math. 4 (1923), 324–328.

- Andrey Kolmogorov, Une série de Fourier–Lebesgue divergente partout, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 183 (1926), 1327–1328

- The first is a construction of an integrable function whose Fourier series diverges almost everywhere. The second is a strengthening to divergence everywhere. In French.

- Lennart Carleson, On convergence and growth of partial sums of Fourier series, Acta Math. 116 (1966) 135–157.

- Richard A. Hunt, On the convergence of Fourier series, Orthogonal Expansions and their Continuous Analogues (Proc. Conf., Edwardsville, Ill., 1967), 235–255. Southern Illinois Univ. Press, Carbondale, Ill.

- Charles Louis Fefferman, Pointwise convergence of Fourier series, Ann. of Math. 98 (1973), 551–571.

- Michael Lacey and Christoph Thiele, A proof of boundedness of the Carleson operator, Math. Res. Lett. 7:4 (2000), 361–370.

- Ole G. Jørsboe and Leif Mejlbro, The Carleson–Hunt theorem on Fourier series. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 911, Springer-Verlag, Berlin-New York, 1982. ISBN 3-540-11198-0

- This is the original paper of Carleson, where he proves that the Fourier expansion of any continuous function converges almost everywhere; the paper of Hunt where he generalizes it to

spaces; two attempts at simplifying the proof; and a book that gives a self contained exposition of it.

spaces; two attempts at simplifying the proof; and a book that gives a self contained exposition of it.

- D. J. Newman, A simple proof of Wiener's 1/f theorem, Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 48 (1975), 264–265.

- Jean-Pierre Kahane and Yitzhak Katznelson, Sur les ensembles de divergence des séries trigonométriques, Studia Math. 26 (1966), 305–306

- In this paper the authors show that for any set of zero measure there exists a continuous function on the circle whose Fourier series diverges on that set. In French.

- Sergei Vladimirovich Konyagin, On divergence of trigonometric Fourier series everywhere, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 329 (1999), 693–697.

- Jean-Pierre Kahane, Some random series of functions, second edition. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-45602-9

- The Konyagin paper proves the

divergence result discussed above. A simpler proof that gives only log log n can be found in Kahane's book.

divergence result discussed above. A simpler proof that gives only log log n can be found in Kahane's book.